Movie Theater Sound: How does Dolby Digital work?

I know many of us haven't been in a theater for a while, so I wanted to write this short missive about the underappreciated world of theater sound before my next product design post drops. If this sort of technical nerdery isn't your thing, I get it. Expect the next post on product development in your inbox next week.

In the early days of movie releases, theaters were largely monaural. The first "surround sound" attempt was Disney's Fantasia. In the 40s it used a 5 speaker array: 3 in the front and 2 in the rear, with the rear channels stored on a separate reel of film. This system was called Fantasound, and it didn't catch on. Fantasound was expensive, and in the end it was only used in two theaters: New York's Broadway Theater and the Carthay Circle Theater in Los Angeles.

Other attempts were made using multiple magnetic tape channels for multiple tracks of audio (think the scratchy-hissy mess of old cassette tapes), or using two optical "stereo" optical tracks with one track being the main movie audio and the second track just for the "surround effects". Neither of these solutions worked well or were widely implemented, and so surround sound as an idea faded out of fashion through the 50s.

This would be the status quo from the 70s. Even when a studio made a magnetic 4 or 7 channel audio score for their film, only large theaters would invest in the technology to play back magnetic audio. In fact, many theaters would only have mono optical audio for their big screens! This is the environment where Dolby Stereo launched.

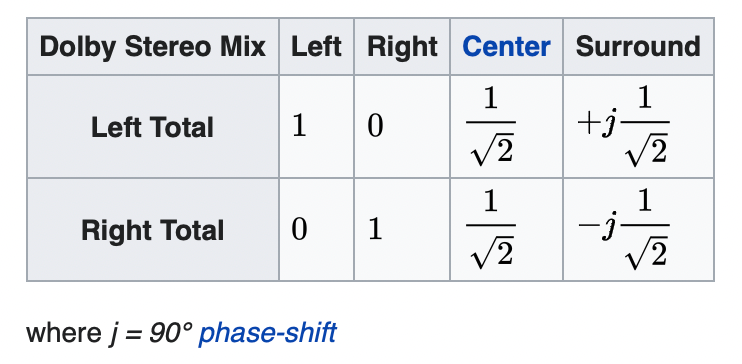

Dolby Stereo used the space of a standard-width mono optical track to encode two discrete stereo channels that could be computed through matrix decoding into 4 channels. If the theater didn't support Dolby Stereo, the tracks would be backwards-compatible to either standard stereo or even all the way back to mono. This was a game changer as it meant a studio only needed to make one 35mm print for all theaters.

Now that all theaters were using film that was capable of 4-channel surround sound, all they needed was an incentive to upgrade their equipment. That incentive would come from a little known and mostly forgotten film released in 1977.

Star Wars made full use of the 4 channel system, and it's stunning mixing quality led to many theaters upgrading. This was further pushed by THX certification, created by George Lucas, to set standards for quality of visual and audio playback in theaters. This led to a greater standardization of the movie going experience.

What's more wild is the last movie you saw before COVID shut down theaters still had a Dolby Stereo track. Nowadays the analogue format is primarily used as a backup in case the digital tracks fail, but they're still there.

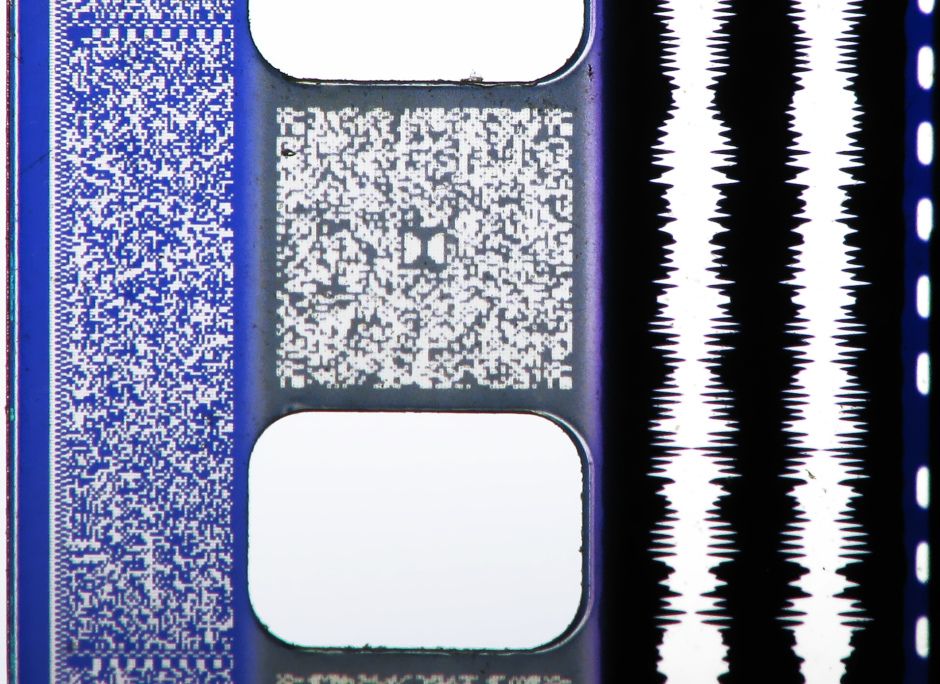

Speaking of digital, this is where things start to get a bit more wild. Dolby Digital 5.1 (starting with Batman Returns) uses data blocks that resemble 2D barcodes between the spokes in the film (complete with an adorable DD logo in the center). These data blocks decode into a 320 kb/s AC-3 audio stream.

DTS uses a separate digital audio track provided by data stored on a CD or Hard Drive that syncs up to the film using time codes printed beside the analogue optical audio track. Sony Dynamic Digital Sound (SDDS) is another competing standard which also uses data blocks and is encoded between the spokes and the outer edge of the film. SDDS was the last to come to market and never had the same adoption as the other two standards. As all 3, and analogue, use different parts of the film all can (and often do) exist on the same print.

Today digital projection is largely replacing film, and as such movies are often delivered on hard drives with their own software and DRM to manage the playback. Some character is definitely lost is the transition to pure digital distribution. If you ask me, digital audio on film just looks cool.

For further listening, I'd recommend a two-part podcast on the THX sound from Twenty Thousand Hertz. Here's part one and part two.